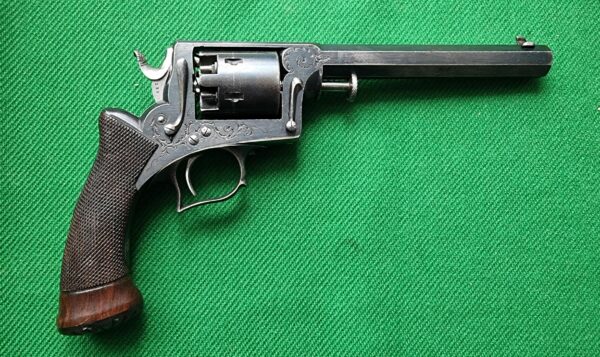

Revolver Pryse & Cashmore 1855

Description

In 1855, Birmingham gunsmith Charles Pryse and West Cashman (Staffordshire) gunsmith Paul Cashmore were awarded British Patent 2018/1855 for a self-centering revolver mechanism and various improvements to revolver designs, as well as improvements to loading levers for revolvers This patent would become the basis for what collectors call the Dawrevolver, a weapon normally attributed to George H. Daw of London, but never made by him. The Pryse & Cashmore design was for an open-top percussion revolver with somewhat unique double-action locking work. Like a traditional “self-locking” revolver, it could be cocked and fired with a single long pull of the trigger. Similarly, the revolver could also be hand-cocked and then fired by pulling the trigger in a conventional single-action mode. These two methods of operation taken together are generally considered to be a traditional double-action revolver. The lock work, however, had an added feature in that pulling the trigger slowly, about halfway to the rear of its full travel, allowed the hammer to engage a notch that left the revolver in a semi-closed position and the partially indexed cylinder. This allowed the cylinder to be manually rotated for loading, but also allowed a shooter to deliberately aim, and then ended the firing sequence by terminating the trigger pull, which indexed and locked the cylinder, fully cocked the hammer, and then released to fire. . This mid-cock position along the trigger pull travel reduced the weight and length of the double-action pull and gave the revolver the speed advantage of a double-action (or self-bearing) revolver as well as the improved accuracy of a single action type trigger. This action was somewhat similar to the “wobble action” used in early Adams and Tranter revolvers. The revolvers were percussion ignition with cylinders that rotated counterclockwise. There were three main components to revolvers: the frame, the cylinder, and the barrel, which also included the cocking lever assembly. The barrel was secured to the frame via a cross wedge that entered from the right side of the gun (Colt entered from the left side) and passed through both sides of the barrel band and cylinder axis pin. An interesting design feature was the “U” shaped notch at the bottom of the hammer nose which was designed to rest on shear pins on the rear face of the cylinder, between the chambers. This allowed the revolver to be safely transported with a fully loaded cylinder, hammer down on a safety pin. This was similar to the safety pin system found on Colt revolvers of the period, but executed in a more elegant manner, making the system more secure and reliable. Like most English revolvers of the time, the Pryse & Cashmore revolver was available in a variety of frame sizes and calibers. Standard models were “Holster” in 38 caliber (approximately .50 caliber), “Army” in 54 caliber (.443″), “Navy” in 80 caliber (.387″), and “Pocket” in 120 caliber (.338 “) And it is even reported that a diminutive .240 caliber (approximately .28 caliber) pocket model was also produced. Barrel lengths varied with caliber and longer barrels were used in the larger calibers. 38 revolver barrels of caliber were typically about 6 ½” in length, although examples over 8″ in length are known. The standard “Army” barrel was 6 ½”, the standard “Navy” barrel was 5 ½” like the standard barrel. “Pocket”. Of course, variations can and do happen, with special barrel lengths and calibers available. The larger calibers were only available with a 5-shot cylinder, while the 120 had a 6-shot cylinder. A variant of the 80 caliber revolver was available with a solid frame, in instead of an open top, and this gun was also available with a 6-shot cylinder. A variety of cocking lever systems are found in Pryse & Cashmore revolvers, including those patented as part of the revolver’s original design, as well as in a design patented by Thomas Blissett. About 5,500 of the patented Pryse & Cashmore percussion revolvers are believed to have been produced from about 1855 to 1865, with the vast majority of them marked by George Daw. A few early examples with other retail brands are known, but Daw certainly had a hand in marketing the vast majority of guns. The Times and the 1860 edition of Hans Busk’s book The