Walch 10 shot belt revolver

Description

Unusual revolver, signed by Walch, patented in 1859, in fact manufactured in Winchester company. It has unusually long cylinder with five chambers. Each one is loaded with superimposed two powder loads and balls. It has 10 percussion nipples and two hammers. They are cocked together. Pressing the trigger always fire the right nipple. The fire channel in cylinder is long and it reaches the front load. Releasing the trigger slightly and pressing again drops the left hammer, which fires the back charge. The gun is in excellent condition. It is belived that 3000 of them were manufactured.

There was also a version in .36 navy caliber, 6 chamber, 12 shot of the same design. It is more scarce, about 200 made and actually used in the Navy.

On February 8, 1859 John Walch of New York City received US Patent #22,905 for a somewhat unique revolver that fired superimposed loads from its cylinder, thus doubling the number of times the revolver could be fired before it was reloaded. Walch’s patent application, describing his Improvement in Revolving Firearms, read in part:

“The nature of my said invention consists in constructing a revolving chamber with two ranges of nipples connecting to the middle and rear part of the breeches, in combination with double hammers so fitted and acting that upon pulling the trigger the hammers fall, the one before the other, and explode caps on the aforesaid nipples that fire in succession charges contained in the forward and rear parts of each breech, so that two charges are fired out of one breech and the breech revolved each time the two hammers are cocked.”

As mid-19th century percussion revolvers were prone to chain fires (the simultaneous detonation of chambers other than the one being fired as a result of the firing of the gun), it would seem that Walch’s double loaded chambers would raise few eyebrows and cause concern among potential users. However, Walch explained clearly in his patent application that there was nothing to fear, as his revolvers would also use a new type of projectile. He notes that this new type of bullet was “made either by attaching a tin plate to a half ball by means of a very thin piece, or by connecting two half-round balls by means of a very small piece, in such a manner as to have a recess all round, This recess is filled with a composition consisting of three-fourths part of soap and one-quarter of oil.” While the description may not really bring to mind what the inventor intended, the patent drawings that he references can best be described as miniature “bar shot” which essentially was a lead ball cut in half and joined by a thin piece between the flat sides that resulted in an incredibly deep groove. This also gave the projectile a more oval than round silhouette. The purpose of this deep groove was to contain the grease like composition described, which would ooze out of the groove when the ball was compressed during loading and the space between the two halves suitably squeezed. This grease would then, in the words of the Walch, have the effect that “…every danger is likewise prevented by which the after-charge might be ignited when the forward charge is fired off….” Walch further notes that this rather slippery arrangement with the heavily greased balls would have the effect that “the chamber will be well greased and the barrel by each discharge will be there by cleaned.” He goes on to further state the advantages of the arrangement being that “as this forms a perfect air-tight packing for the ball the powder will have more force (and) be able to send the ball a greater distance.” It is interesting to note that while Walch appears to have, at least in his mind, removed the possibility of the rear charge firing as a result of the front charge being fired, he does not address the possibility that the front charge might misfire, and when the rear charge was fired into the blocked chamber, a catastrophic failure would almost certainly occur.

Walch knew that the concept of a superimposed positioning of two or more loads in a single chamber was not a new idea and did not claim that design in his patent. In fact, the US military had experimented with the concept circa 1829 with the Ellis-Jennings repeating rifle, which was produced in both four and ten shot variants. Rather his claim ran specifically to the arrangement of two rows of nipples on the rear of revolving cylinder allowing double loads to be fire from each cylinder chamber. His other claim referred to his trigger, which as he notes, “is on its upper end made in two parts.” Thus, a single conventional trigger appeared in the triggerguard, which had two operating parts in the frame, which allowed the release of the right and then the left hammer with two distinct pulls.

John Parker Lindsay received a similar patent, #30,332 on October 9, 1860 that covered a single trigger mechanism that could release two or more hammers in sequence. This was a more elegant solution to the single trigger and double hammer firing mechanism. It appears that the two men would design a refined version of the Walch revolver together. The revolver conceived by these two New Yorkers would eventually be brought to Oliver Winchester and the New Haven Arms Company to manufacture, and the Walch Pocket revolver almost prevented the Winchester Firearms Company from existing; but we are getting slightly ahead of our story.

Like many designers and patent holders during the 19th century, Walch had plenty of ideas but no manufacturing facilities. To that end he entered into an agreement with the Union Knife Company of Naugatuck, CT to manufacture the first of his double-load revolver designs, the Walch “Navy” Revolver. This was a .36 caliber, six-shot chambered revolver that was capable of firing twelve shots out of the double loaded cylinder chambers. The revolver was roughly 12 ¼” in overall length with a 6” octagonal barrel and utilized two triggers rather than the convoluted single trigger with two upper sections, as shown and described in Walch’s patent application. The production of the Walch Navy revolver at the Union Knife Company was supervised by John Parker Lindsay, who would become famous (or infamous) for his Lindsay Model 1863 Rifle Musket that used a double loaded chamber incorporated into a US M1863 pattern musket with double hammers and a single trigger. While Flayderman’s Guide To Antique American Arms suggests that Lindsay was already producing his Young American pistols based upon the single trigger, double-hammer, double-loaded concept at the Union Knife Company before Walch came to the company, it seems more likely that the former Springfield Armory employee was initially engaged to produce the Walch contract revolvers at the Union Knife Company, more than a year and half prior to starting to produce his own Young American pattern pistols at the same facility. The Walch patent pre-dates Lindsay’s by some nineteen months, so it seems unlikely that Lindsay was already producing his firearms prior to meeting Walch. In fact, the pocket version of the Lindsay Young American pistol bears the February 8, 1859 patent date of Walch’s design along with the October 9, 1860 date of Lindsay’s design under its barrel.

Despite producing a small number of the .36 caliber Walch Navy revolvers being produced at Union Knife Company circa 1860, they met with little commercial success. While exact production figures are not known, most reference suggest less than 300 of the Walch Navy revolvers were manufactured. During the same basic period Lindsay produced a similar number (possibly as many as 400-500) of his Young American pocket pistols and approximately 100 of his larger sized Belt model pistols; both of which also seem to have been commercial failures. By early 1861, the Union Knife Company seems to have separated themselves from both Walch and Lindsay and returned their attention to producing the knives that were the heart and soul of their business, rather than speculating in the production of odd ball handguns.

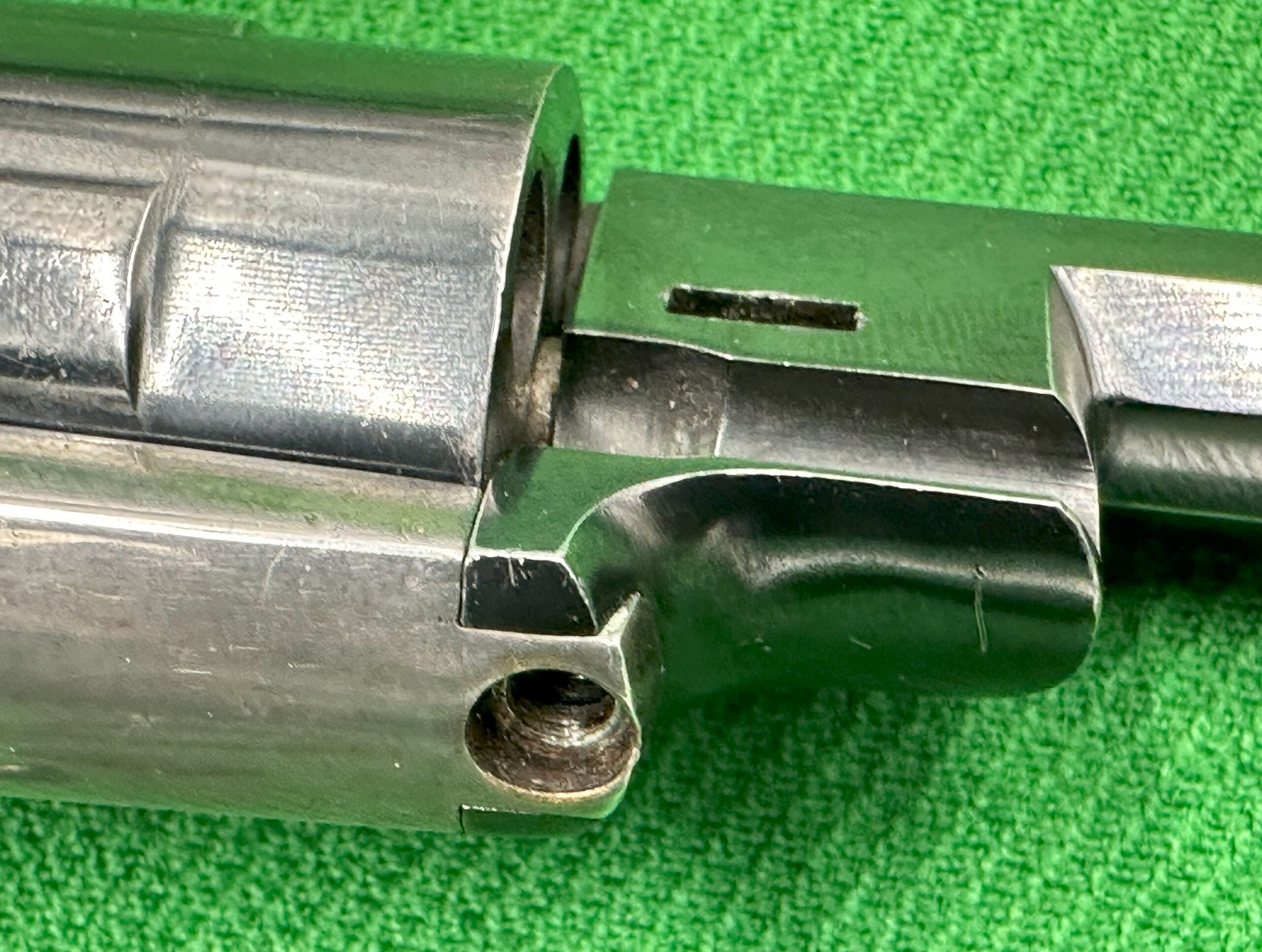

However, Walch was not to be deterred. A new pocket version of the Walch revolver had been designed that was almost certainly a collaboration between Walch and Lindsay. The new revolver was .31 caliber and was initially produced with a brass, rather than an iron frame. The first 1,500 to 2,000 guns were produced with a brass frame, but the balance of production were made with an iron frame. The open top design used both a wedge and a screw in the bottom of the frame to secure the barrel to the frame. The revolver had a 3 ¼” octagonal barrel and a five chambered cylinder that allowed ten rounds to be fired from the gun. Like its predecessor it retained the double hammer arrangement, but the double triggers and triggerguard were abandoned for a single spur trigger mechanism that resembled that used on the Lindsay pistols and was likely of his design. The ten percussion nipples on the rear of the cylinder alternated ignition of the two rounds in the chamber. The first nipple sent its flame into an extended flash channel that traveled along a small hump, much like an inverted cylinder flute, towards the chamber mouth, where it fired the front or first charge. The second nipple fired directly into the rear of the cylinder to detonate the rearmost second charge. As before, Walch had no capability to manufacture the new design, so he approached the New Haven Arms Company of New Haven, CT. to manufacture the guns.

The New Haven Arms Company was in a state of flux at this time, in dire financial straits and was on the verge of collapse. The company had been formed in 1857 from the remains of the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, which itself evolved from the first version of the Smith & Wesson firm. In all cases, the companies were trying to produce and market innovative repeating arms that were inherently hobbled by their low powered Rocket Ball cartridge. As Oliver Winchester would opine in a letter a major stockholder of the New Haven Arms Company in October of 1862:

“…the company (New Haven Arms) commenced manufacturing the Volcanic firearms, starting a large lot of each size and in about 18 months thereafter began to turn out finished arms, and put them on the market. They at once found a strong prejudice against them among dealers, and [following] a few months vain efforts to sell them, became satisfied that there were radical defects which would prevent their ever becoming a salable article. We, of course, had no way but to finish up those we had commenced, as they would have been a total loss if we dropped them. This involved a large outlay. Most of that stock has been sold at a heavy loss, and nearly all of the costly tools and machinery for making them were rendered useless. While finishing up these arms (taking about two years), we perfected and patented certain improvements (Dec. 1860), obviating the objections to the old arms, and making a perfect thing as applied to the rifle.”

This was the situation that Walch found Winchester in when he approached New Haven Arms. The firm was cash strapped from the failure of the Volcanic project, was sitting on a large investment in machinery that was now of limited utility but saw the potential for their newly patented Henry Rifle to save the company. All New Haven Arms needed was an injection of capital to re-tool for the new production model. As the company had a rocky history with its investors, it was not likely to find new capital from the old sources. As a result, Oliver Winchester agreed to manufacture the new pocket revolver design for Walch. As Winchester continued to explain in the same letter quoted above:

“At this point we were too much exhausted, as we felt, to proceed in getting up the tools and fixtures to manufacture the [Henry] rifle, but let them lay, and took a contract to make 3,000 revolvers for a party in New York [John Walch .31 caliber 10 shot revolvers, patent of Feb. 8th 1859] calculating to clear some $8,000 upon the same (amounting [to sales of] $26,000). But when the pistols were finished, the party failed to respond. We now have them on hand and consequently the capital they cost locked up in a lawsuit.”

As a result of Walch’s default on the contract with New Haven Arms, he had all but pushed the fiscally unstable company over the brink of total financial ruin. Oliver Winchester’s company now had some additional $18,000 tied up in 3,000 Walch Pocket Revolvers, and worse than that, was not able to offer them on the market as the revolvers themselves were tied up in a lawsuit! It would be nearly another year, July of 1863, before Winchester was able to start selling the revolvers. However, as before with the Walch Navy, sales were lackluster. New Haven Arms tried to market the revolvers with a suggested retail price of between $15 and $18 each and did manage to get a sales agent to take 125 units in July of 1863 at a price of $8.80 each. If the firm could sell the guns for that price, they would gross $26,400; some $400 more than the original business plan. However, the distributor had a hard time finding willing buyers and returned nearly two-thirds of the guns, 80 in all, unsold. How, when and where New Haven Arms managed to sell their remaining inventory of Walch Pocket Revolvers is unclear.

Robert Reilly in his book United States Military Small Arms 1816-1865 notes that some of the Walch Pocket revolvers were acquired by the 9th Michigan and 14th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiments, but he asserts that these were certainly personal purchases and not state of Federal government purchases. As handguns were not regularly issued or carried by infantry, this seems quite logical. However, Flayderman states categorically that “One entire outfit, Company I of the 9th Michigan Infantry armed themselves with the gun, where it received favorable comment.” He continues, “Not all field reports were so laudatory.” As no citation is provided and I have not been able to confirm this purchase in any period document, I am somewhat skeptical that an entire infantry company carried these pocket revolvers, but it is possible. Such purchases were sometimes the type of action that was undertaken by a wealthy company commander who was willing to help equip his troops from his own pocket.

Thus, the story of one of the more bizarre revolver designs of the mid-19th century comes to a close. Walch’s default on the New Haven Arms contract almost caused that company to fail, and if it had done so, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company may have never been born. This strange story makes the Walch not only an important piece of firearms curiosa from a design standpoint but means that these revolvers belong in a collection and display of early “Winchester” arms, along with the Volcanic and Henry firearms produced by the New Haven Arms Company.

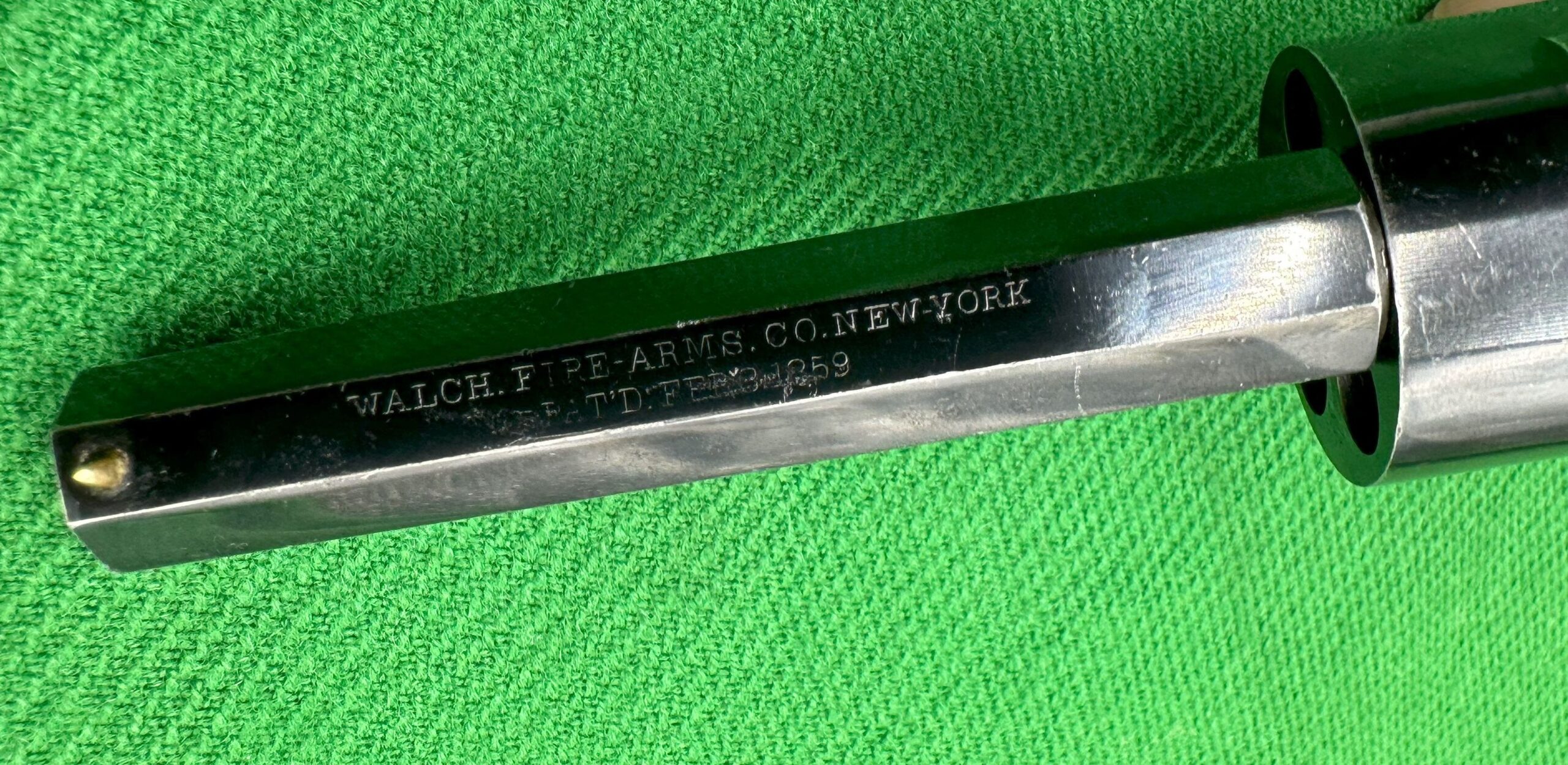

Offered here is a FINE condition example of a brass frame, early production Walch 10-Shot Pocket Revolver. The gun is one of the brass framed examples and is serial number 678, making it a fairly early production gun. The revolver is serial numbered on the lower left side of the frame, under the grip. It is also serial numbered on the top of the cylinder arbor and inside both grips. The top of the 3 ¼” octagonal barrel is clearly marked in two-lines:

WALCH FIRE-ARMS CO. NEW-YORK

PAT’D FEB. 8, 1859

The revolver retains a nice amount of thinned and faded original, blue, somewhere between 10% and 20% overall on the barrel and cylinder. The blue is most prevalent in the protected areas around the web of the barrel and along the raised edges of the flash channels that run to the forward part of the cylinder. The balance of the iron parts have a really attractive plum brown patina that blends with the blue giving the gun the appearance of having more finish than it really does. The brass frame has an absolutely gorgeous butterscotch patina that is really attractive and appears completely untouched. The metal is mostly quite smooth, with some evenly distributed flecks of pinpricking on the barrel and cylinder and a couple of spots of more notable, light pitting on the barrel. The metal shows a few scattered, light impact marks, especially around the wedge. The revolver retains its original brass cone front sight and has a fine bore that remains mostly bright with some scattered oxidation and minor discoloration but would likely clean up some with a good brushing. The revolver is mechanically functional, but as is so often the case with Walch revolvers the timing and indexing are not quite perfect, and the cylinder needs a little nudge to fully rotate into the correctly indexed position for firing. The dual hammers operate correctly and fall as they should, right then left, after two consecutive pulls of the spur trigger. The grips are in about VERY GOOD condition. They are mostly crisp with much of their original varnish remaining. They show scattered impact marks on their bottoms and these marks continue up the side of the left grip to the screw. The left grip also has a small chip out of the bottom of the leading edge. As would be expected the grips also show scattered minor bumps, dings and mars.

Overall, this is a really attractive example of a scarce brass frames John Walch 10-Shot Pocket Revolver. It has a very pleasing look with some nice original blue, clear markings and a really attractive patina on the brass frame. These guns do not come up for sale very often and when they do, they are often in rough shape and have major mechanical issues. This one is all complete and correct, is essentially functional and has a ton of eye appeal. It would be a fine addition to any collection of Civil War era percussion revolvers, a collection of firearms curiosa, or as an example of a gun produced by the New Haven Arms Company that almost kept the Winchester Firearm Company from ever existing!